- Home

- Greek Ruins in Sicily

- Selinunte Park

Selinunte Park: Ancient Ruins by the sea

Welcome to the Selinunte park where the Mediterranean wind carries whispers of vanished grandeur, where the sea-salt air mingles with the scent of wild fennel—'selinon' in the ancient tongue—from which this city drew its name.

The archaeological park spans 270 hectares of coastal Sicily. It encompasses the remains of one of the most powerful Greek colonies in the western Mediterranean, founded in 628 BCE by settlers from Megara Hyblaea.

Here, limestone columns rise against cerulean skies; the earth yields pottery shards and votive offerings still, the weight of twenty-seven centuries pressing through the soles of your feet.

We stand where Carthaginians razed temples, where earthquakes toppled what war had spared, where time itself has become the final architect of ruin.

The view from the Acropolis towards the eastern hill of the park. On the right, you have the village of Marinella and one of the beaches right next to the park.

The view from the Acropolis towards the eastern hill of the park. On the right, you have the village of Marinella and one of the beaches right next to the park.History of Selinunte

Selinunte's history is a narrative of rise, zenith, and catastrophic fall, a trajectory that haunts the ruins with particular poignancy.

Founded in the seventh century BCE by Greek colonists seeking agricultural land and trade opportunities, the city flourished rapidly, its wealth derived from grain exports, wine, olive oil, and its strategic position on the southern Sicilian coast.

By the fifth century BCE, Selinunte had become one of the wealthiest cities in the Greek world, its temples rivaling those of mainland Greece in scale and ambition.

Yet prosperity bred conflict: territorial disputes with the neighboring Elymian city of Segesta escalated into open warfare, drawing in the great powers of the age.

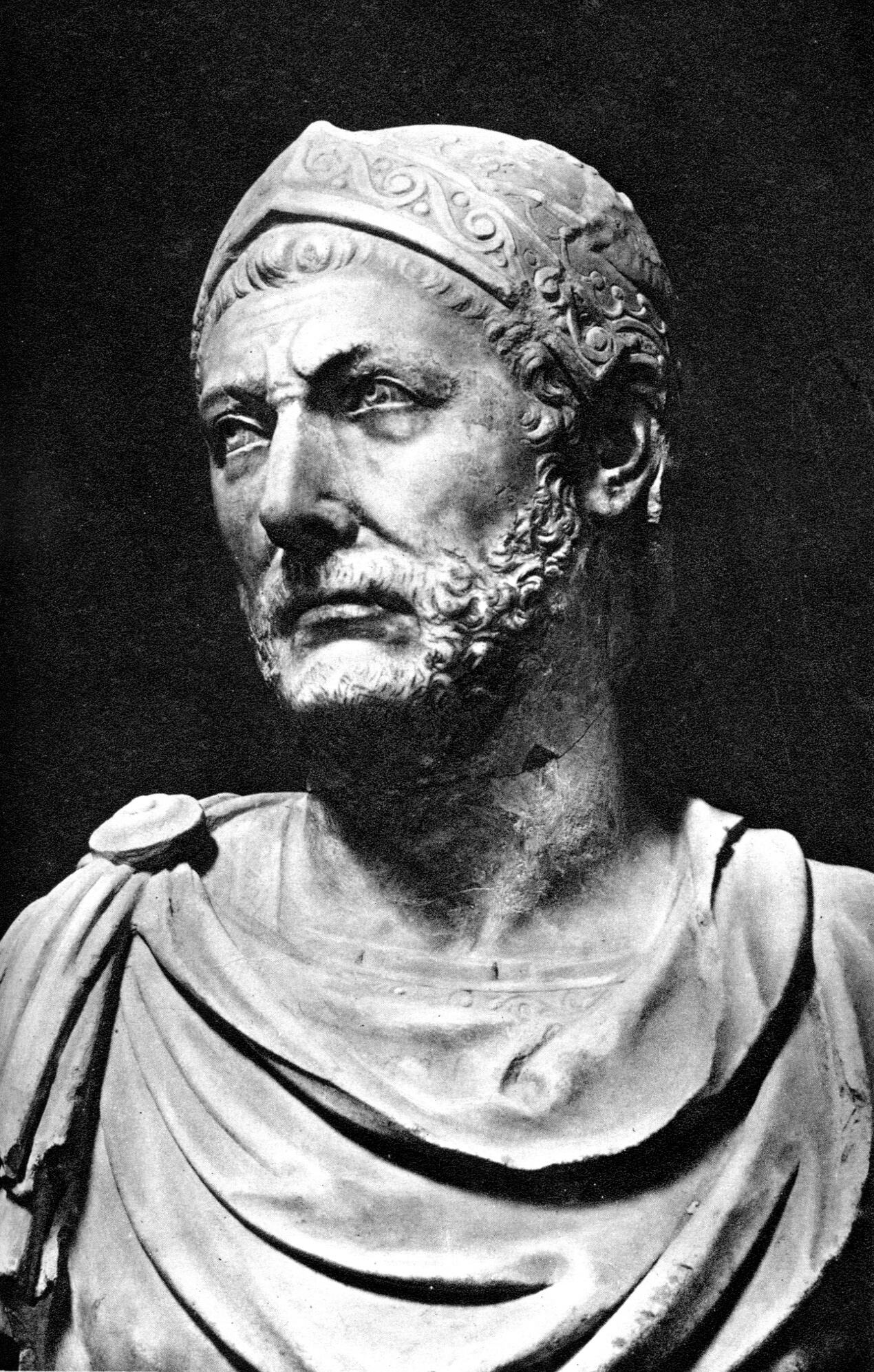

In 409 BCE, Segesta appealed to Carthage for aid; the Carthaginian general Hannibal Mago besieged Selinunte with an army of 100,000 men.

The city fell after nine days of brutal fighting; sixteen thousand inhabitants were slaughtered, five thousand enslaved. The temples were desecrated, the walls breached, the city left in ruins.

A remnant population returned and rebuilt on a smaller scale, but Selinunte never regained its former glory.

In 250 BCE, during the First Punic War, the Carthaginians forcibly evacuated the remaining inhabitants to prevent the city from falling into Roman hands.

Hannibal.

Hannibal.Selinunte was abandoned, left to the encroaching sand and the relentless Mediterranean winds. Earthquakes in the medieval period—particularly a catastrophic tremor in the sixth or seventh century CE—toppled most of the standing structures, reducing the temples to the picturesque ruins we see today.

For centuries, the site served as a quarry; locals carted away dressed stones to build farmhouses and churches. Only in the nineteenth century, with the advent of archaeological science and Romantic interest in ruins, did Selinunte begin to be systematically excavated and protected.

The work continues: each season brings new discoveries, new fragments of the puzzle.

The Four Zones of Selinunte Park

Selinunte park is divided into four principal zones: Eastern Hill with its colossal temples; Acropolis overlooking the harbor; the ancient city's residential quarters; and the Sanctuary of Malophoros to the west, across the now-dry Modione River.

Between these zones stretch olive groves and Mediterranean scrubland, pathways of compacted earth that turn to dust beneath the summer sun.

There are two ways to cover the park: either walk or rent a golf cart. The distances are not trivial: nearly two kilometers separate the easternmost temples from the western sanctuary.

Wear sturdy shoes, bring water, and wear a wide-brimmed hat. The Sicilian sun shows no mercy to the unprepared, and shade is scarce among these fallen stones.

Temple E on the eastern hill of Selinunte Park (Temple of Hera).

Temple E on the eastern hill of Selinunte Park (Temple of Hera).Temples on the Eastern Hill

The Eastern Hill, right by the main entrance, is where three temples stand in varying states of preservation, designated by archaeologists with the stark nomenclature of letters: E, F, and G.

Temple E, reconstructed through anastylosis—the painstaking reassembly of original fragments—between 1956 and 1959, rises complete once more, its peristyle of thirty-eight Doric columns restored to vertical glory.

While circling its platform, the 'stylobate', measuring forty-five meters in length, one observes how the columns taper with mathematical precision, how the 'entasis'—that subtle convex curve—corrects the optical illusion of concavity that would otherwise plague straight lines.

This temple, likely dedicated to Hera, goddess of marriage and childbirth, dates to 460–450 BCE, the high classical period when Greek architecture achieved its most refined proportions.

As one stands beneath the eastern pediment at dawn, when rose-gold light floods through the colonnade, he will understand why the ancients built their sanctuaries facing the rising sun. The temple breathes with the day's beginning; it exhales shadows and inhales luminescence.

Walking among the ruins of the Temple of Zeus. There are lots more stones behind this first heap of rocks.

Walking among the ruins of the Temple of Zeus. There are lots more stones behind this first heap of rocks.Temple G - probably dedicated to Zeus - by contrast, remains a magnificent wreckage, its drums and capitals scattered across the ground like the bones of some primordial giant.

This was among the most prominent Greek temples ever attempted, rivaling even the Olympieion at Agrigento, with a platform stretching 110 meters long and 50 meters wide.

Construction began around 520 BCE and continued for decades, perhaps a century, yet the temple was never completed; the Carthaginian sack of 409 BCE interrupted the work forever.

You can walk among column drums eight feet in diameter, each weighing upward of one hundred tons, and marvel at the engineering prowess required to quarry, transport, and lift such masses without modern machinery.

Wooden cranes, bronze pulleys, rope, and human muscle, the slow accumulation of stone upon stone—this was the technology of the miraculous.

Between these monuments, Temple F stands smaller, more intimate, its ruins less legible to the untrained eye. Dedicated perhaps to Athena or Dionysus—the evidence remains ambiguous—it dates to the mid-sixth century BCE.

Here you'll find only foundations and scattered architectural members. Yet, even in this state of dissolution, the temple's proportions speak of harmony, of that masterful balance between mass and void that defines the Doric order.

The Acropolis

From the Eastern Hill, we turn westward toward the heart of ancient Selinunte: the Acropolis, a fortified plateau rising above the now-silted harbor.

The Selinunte Acropolis was the city's ceremonial and civic nucleus, enclosed by massive defensive walls constructed in the fourth century BCE, after the Carthaginian destruction necessitated rebuilding.

Five temples cluster here, labeled A through D and O, their proximity suggesting a sacred precinct of extraordinary density.

Temple C, the oldest and most sacred, dominated the skyline from its construction around 550 BCE; its metopes—sculptural panels depicting mythological scenes including Perseus slaying Medusa and Herakles subduing the Cercopes—now reside in Palermo's archaeological museum, removed in the nineteenth century for preservation.

This is where those metopes once hung, the polychrome brilliance now faded to museum sterility: red, blue, gold leaf catching the afternoon light.

The Selinunte temple ruins on the Acropolis overlap and interpenetrate, evidence of continuous building, destruction, and rebuilding across four centuries.

Wondering at the remnants of an ancient Acropolis.

Wondering at the remnants of an ancient Acropolis.Temple D, oriented north-south rather than the canonical east-west, suggests a dedication to a chthonic deity, perhaps Demeter or Persephone, goddesses of the underworld and agricultural fertility.

Temple A, with its elegant proportions and late-fifth-century date, may have honored Apollo or another Olympian.

Temple O, the smallest, nestles against the northern fortifications.

As you move among these foundations, you can still trace the ghostly outlines of 'cellae'—the inner chambers that once housed cult statues—and 'pronaoi', the entrance porches where priests performed their rites.

The limestone underfoot is worn smooth by millennia of wind and rain, by the passage of countless feet: ancient worshippers, medieval scavengers, Renaissance antiquarians, modern tourists.

Residental Quarters

North of the Acropolis temples, the residential quarters sprawl in a grid of streets and insulae, the city blocks where merchants, artisans, and citizens lived their quotidian lives.

Here, the past becomes tangible in a different register: not the sublime grandeur of temples but the humble materiality of daily existence. This is where bread was baked, where wine was stored, and where children played in narrow alleys.

The city was home to perhaps twenty-five thousand souls at its zenith. In this cosmopolitan port, Greek, Phoenician, and indigenous Elymian cultures mingled and traded.

The Sanctuary of Malophoros

To reach the Sanctuary of Malophoros, we must cross the Modione River valley—dry in summer, a sluggish stream in winter—and ascend the western plateau.

The walk takes twenty minutes, longer if we pause to examine the necropolis that lines the ancient road. Here, in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, the dead were interred in chamber tombs cut into the bedrock, their grave goods—pottery, jewelry, weapons—accompanying them into the afterlife.

The sanctuary itself, dedicated to Demeter Malophoros, "bearer of the apple" or "bearer of flocks," was a place of female worship, where women came to pray for fertility, for successful childbirth, for the prosperity of their households.

Here, you'll stand before the altar —a massive stone table where sacrifices were made. Can you feel the accumulated weight of devotion, the hopes and fears of women whose names are lost but whose prayers linger in the stones?

Tips for Visiting the Selinunte Park

Practical considerations assert themselves: Selinunte park opens daily, with hours varying by season—typically 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM in summer, closing earlier in winter months.

Confirm current schedules before your visit, as Italian cultural sites may close irregularly for holidays and maintenance.

The entrance fee is modest, approximately ten to twelve euros for adults, with reductions for students, seniors, and EU citizens under eighteen. Purchase tickets at the main entrance near the Eastern Hill or, increasingly, online in advance to avoid queues during peak season.

The park offers minimal facilities; near the entrance, you have restrooms and a bookshop stocking guides and scholarly texts. No restaurants operate on-site; for them, you have to go to nearby Marinella. Plan accordingly.

The roads inside Selinunte park are mostly paved. If you plan to explore the whole area, you will need to do quite a bit of walking.

The roads inside Selinunte park are mostly paved. If you plan to explore the whole area, you will need to do quite a bit of walking.Guided tours in multiple languages depart regularly from the entrance, led by licensed archaeologists who illuminate the ruins with historical context and anecdotal detail.

It is recommended that you engage a guide for your first visit; the stones speak more eloquently when their stories are narrated. Alternatively, audio guides are available for rent, though they lack the responsiveness and depth of a human interpreter.

Allow at least 3 hours for a thorough exploration; longer if you wish to visit all 4 zones. The ambitious visitor who walks from the Eastern Hill to the Sanctuary of Malophoros and back will cover five to six kilometers; pace yourself.

The park is broadly accessible, with paved paths connecting the major monuments, though some areas—particularly the residential quarters and the Malophoros sanctuary—require walking on uneven terrain.

Visitors with mobility limitations should focus on the Eastern Hill and the Acropolis, where the principal temples are easily reached. Wheelchairs and strollers can navigate the main routes, though assistance may be necessary on steeper gradients.

Shade is scarce; the Sicilian sun in July and August can be punishing, with temperatures easily exceeding thirty-five degrees Celsius. Visit in the morning or late afternoon, when the light is kinder and the heat less oppressive.

Spring (April–May) and autumn (September–October) offer ideal conditions: mild temperatures, wildflowers in bloom, and fewer crowds.

Winter visits are possible but less atmospheric; the site can feel desolate under gray skies, though some find beauty in that melancholy.

The park is accessible by car via the SS115 coastal highway; parking is available at the main entrance. Public transportation is limited: buses run infrequently from Castelvetrano, the nearest rail station, so careful schedule coordination is required.

Renting a car is advisable for flexibility and access to other western Sicilian sites—Segesta, Agrigento, Mozia—that complement a visit to Selinunte.

Pack essentials for your visit: sunscreen, a hat, comfortable walking shoes, water, and snacks.

A camera is indispensable; the play of light on the ruins shifts hourly, offering endless photographic opportunities.

Conclusion

As we depart Selinunte park, the temples recede behind us, their columns silhouetted against the western sky, and we carry with us the strange, nostalgic ache that ruins inspire—a longing for a past we never knew, a mourning for a grandeur that was never ours to lose.

Yet the stones remain, patient and enduring, waiting for the next generation of pilgrims to trace the outlines of what was and imagine what might have been.

This is the gift of Selinunte: not answers, but questions; not certainty, but wonder; not the past restored, but the past made present, immediate, and achingly real.

Go, walk among the ruins, and let them speak to you in their silent, eloquent tongue.

(November 14, 2025)

Recent Articles

-

Festivals in Sicily: Dates, Rites & Travel Planning

Feb 11, 26 09:22 AM

Festivals in Sicily help you time your visit for processions, performances, and street food—season by season. -

Taormina: Is It Worth It on Your Sicily Itinerary?

Feb 07, 26 11:11 AM

Wondering if Taormina belongs on your Sicily trip? Explore beaches, shopping, and sights—then choose well. -

Car Rental in Sicily: A Traveler’s Guide

Feb 04, 26 01:09 PM

Planning car rental in Sicily? Learn costs by season, insurance basics, required documents, and more.

Follow MANY FACES OF SICILY on Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky & Tumblr

Contact: vesa@manyfacesofsicily.com