- Home

- Castles in Sicily

Castles in Sicily: memories carved in stone

We stand at the threshold of an island where history has inscribed itself in limestone and volcanic rock, where fortresses rise from cliffs like petrified sentinels guarding secrets older than human memory.

Sicily—that triangular jewel suspended in the Mediterranean's cerulean embrace—holds within its rugged topography a constellation of castles, each one a testament to conquest, ambition, and the inexorable passage of empires.

These Castles in Sicily are not mere tourist attractions - although they are that too - but sacred repositories of human struggle, architectural marvels that whisper tales of Norman knights, Arab emirs, and Spanish viceroys who walked their battlements centuries before our arrival.

The island's strategic position—equidistant from three continents, a maritime crossroads—ensured that every Mediterranean power coveted its shores.

Consequently, the castles we encounter today bear the palimpsest of multiple civilizations: Byzantine foundations overlaid with Arab innovations, Norman grandeur crowned by Swabian refinement, Spanish fortifications grafted onto earlier structures.

To visit these Sicilian castles is to traverse not merely geographic space but temporal strata, descending through layers of human endeavor like an archaeologist excavating consciousness itself.

View of the town from Enna's Lombard Castle.

View of the town from Enna's Lombard Castle.Lombardy Castle in Enna

Let's begin our pilgrimage at Castello di Lombardia in Enna, perched atop the island's geometric center at an elevation of 970 meters above the distant sea.

This colossal fortress—one of Sicily's largest medieval strongholds—dominates the surrounding landscape with an authority that borders on the supernatural. Six towers remain of the original twenty, their crenelated crowns piercing the sky like broken teeth in a giant's jaw.

Walk the inner courtyards where Frederick II of Hohenstaufen once held court, where the Holy Roman Emperor contemplated philosophy and falconry between campaigns. The wind here carries the scent of wild fennel and sun-warmed stone; it moans through arrow-slits with a sound almost human, almost plaintive.

Can you feel the weight of centuries pressing down upon these ramparts?

Ursino Castle in Catania

Descend now to Catania's eastern shore, where Castello Ursino squats amid the modern city's chaos like a defiant cube of dark lava stone.

Built in the thirteenth century by Frederick II, this castle once stood at the water's edge; the catastrophic eruption of Mount Etna in 1669 buried its foundations beneath rivers of molten rock, pushing the coastline seaward by half a kilometer.

The fortress survived, entombed but intact, a monument to human presumption before nature's sublime indifference.

Today it houses the Civic Museum, its vaulted halls filled with Greek amphorae and Roman sarcophagi, but the castle itself remains the primary artifact—a study in geometric perfection, four cylindrical towers anchoring a square keep, each angle calculated for maximum defensive efficiency.

Ursino Castle in Catania. (Wikimedia Commons/Effems)

Ursino Castle in Catania. (Wikimedia Commons/Effems)Castle of Venus in Erice

The best castles in Sicily are those that balance architectural significance with narrative resonance, and Castello di Venere (Castle of Venus) in Erice achieves this equilibrium with haunting grace.

Perched 750 meters above Trapani on Monte San Giuliano's summit, this Norman fortress occupies the site of an ancient temple dedicated to Venus Erycina, the goddess of love in her most primordial, chthonic aspect.

The castle's foundations incorporate megalithic blocks from that earlier sanctuary; walk the perimeter and place your palm against stones cut by Elymian hands three millennia past.

On clear days, the view encompasses the Egadi Islands floating like mirages in the cobalt expanse, the salt pans of Trapani gleaming white as bone, the distant smudge of Tunisia on the southern horizon.

Fog descends here without warning, transforming the castle into an island suspended in cloud.

Erice castle and view.

Erice castle and view.Maniace Castle in Syracuse

And then there is Castello di Maniace in Syracuse, that austere quadrilateral rising from Ortygia's southern tip where the Ionian Sea crashes against limestone foundations with percussive regularity.

Emperor Frederick II commissioned this fortress in 1232, naming it for George Maniakes, the Byzantine general who reconquered the city from Arab control in 1038.

The castle's architecture embodies Swabian rationalism: a perfect square, twenty meters per side, with circular towers at three corners and a massive portal that once featured bronze doors looted from Constantinople.

From Maniace Castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Zde)

From Maniace Castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Zde)Caccamo Castle

In Caccamo, 37 kilometers southeast of Palermo, Castello di Caccamo sprawls across a limestone outcrop, with the organic complexity of a medieval town compressed into its defensive architecture.

This labyrinthine fortress—one of Italy's best-preserved Norman castles—contains over one hundred rooms distributed across multiple levels, a vertical maze of barrel-vaulted corridors, spiral staircases worn concave by centuries of footfalls, and chambers that open unexpectedly onto vertiginous views of the Torto River valley below.

The castle's strategic importance derived from its position controlling the route between Palermo and the island's interior; its architectural significance lies in the accretion of styles across eight centuries of continuous habitation and modification.

Caccamo Castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Peppesev)

Caccamo Castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Peppesev)The Castle of Sperlinga

Castello di Sperlinga occupies a category unto itself—a fortress not built upon rock but carved from it, excavated from the living sandstone of a conical hill in the Nebrodi Mountains.

The castle's origins recede into prehistory; its grottoes and chambers were inhabited in Sicel times, expanded by the Byzantines, and fortified by the Normans.

During the Sicilian Vespers of 1282—that island-wide uprising against French Angevin rule—Sperlinga's garrison remained loyal to the occupiers, sheltering them within the rock's embrace while rebellion raged across Sicily.

An inscription above the entrance used to commemorate this defiance: "Quod Siculis placuit sola Sperlinga negavit" (What pleased the Sicilians, Sperlinga alone denied).

Walk through chambers where walls, floors, and ceilings are continuous stone, where human habitation has been subtracted rather than added to the landscape.

A view over Sperlinga, from the castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Azotoliquido)

A view over Sperlinga, from the castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Azotoliquido)Milazzo Castle

We turn now to Castello di Milazzo, a fortified complex sprawling across the summit of a promontory that juts into the Tyrrhenian Sea like a ship's prow aimed at the Aeolian Islands.

This is not a single castle but a palimpsest of fortifications: Greek walls underpin an Arab tower; Norman keeps rise beside Spanish bastions; a seventeenth-century citadel crowns the ensemble.

The complex encloses an area of seven hectares, its perimeter walls extending for fifteen hundred meters, punctuated by seven gates and innumerable towers.

Climb to the highest ramparts and observe how the fortress commands the strait between Sicily and Calabria, that narrow passage through which all maritime traffic between eastern and western Mediterranean must flow.

Before you go, check whether any events are taking place at the castle, as it may be closed to visitors.

Milazzo Castle.

Milazzo Castle.Donnafugata Castle

Castello di Donnafugata near Ragusa presents an anomaly in our catalog—a nineteenth-century aristocratic residence masquerading as a medieval castle, a romantic confection of neo-Gothic whimsy and Venetian Gothic elegance.

Yet we include it for the window it opens onto Sicily's complex relationship with its own past, the way each generation reimagines and reconstructs the island's heritage according to contemporary desires.

The castle's name—"Donnafugata," woman fled—derives from the Arabic "Ayn-as-jafat" (source of health), corrupted through centuries of linguistic transformation into a narrative of female escape.

Walk the labyrinthine garden, designed to confuse and delight, where stone walls form a maze and hidden grottos offer respite from the summer sun.

Castello Donnafugata.

Castello Donnafugata.Norman Castle of Aci Castello

In Aci Castello, a coastal town north of Catania, the Castello Normanno rises from a basalt promontory thrust up from the sea by a prehistoric volcanic eruption.

This fortress—built in 1176 atop a plug of columnar basalt—exemplifies the Norman genius for exploiting natural defensive positions. The castle's foundations merge seamlessly with the volcanic rock, as if the structure had crystallized from molten stone rather than been constructed by human hands.

Climb the weathered steps to the summit and feel the castle sway imperceptibly with the wind, or perhaps with the earth's subtle tremors, for we stand here on the flank of Mount Etna, Europe's most active volcano, whose presence dominates the eastern horizon like a sleeping god.

Norman Castle of Aci Castello. (Wikimedia Commons/gnuckx)

Norman Castle of Aci Castello. (Wikimedia Commons/gnuckx)Falconara Castle in Butera

Castello di Falconara, perched on a cliff overlooking the southern coast between Gela and Licata, offers a study in isolation and melancholy grandeur.

This fourteenth-century fortress—later transformed into a baronial residence—stands sentinel over a pristine beach where sea turtles still nest in summer months.

The castle's remote position, accessible only by a single winding road, preserved it from the worst depredations of modernity; today, it also operates as a hotel, allowing visitors to inhabit its chambers and walk its battlements as temporary castellans.

Stand on the seaward terrace at dusk and watch the sun descend into the Mediterranean, painting the waves with molten copper. At the same time, the castle's shadow lengthens across the sand, like a sundial marking the day's end.

Time moves differently within these walls.

Falconara Castle in Butera. (Wikimedia Commons/pinobarile)

Falconara Castle in Butera. (Wikimedia Commons/pinobarile)Castle of Carini Near Palermo

We conclude our survey with Castello di Carini, twenty kilometers west of Palermo, a fortress whose fame rests less on architectural distinction than on the dark legend inscribed in its stones.

Here, in 1563, the Baroness of Carini—Laura Lanza—was murdered by her father after he discovered her in flagrante delicto with her lover. The bloodstain from her death, according to local tradition, reappears periodically on the castle walls despite repeated attempts to efface it, a crimson stigmata marking the site of passion and violence.

Whether one credits such supernatural persistence or not, the story illuminates an essential truth about Sicilian castles: they are not merely military or residential structures but stages upon which human drama—love, betrayal, ambition, revenge—has played out across centuries.

The stones remember what we choose to forget.

Carini Castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Margherita Scalici)

Carini Castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Margherita Scalici)Castles in Sicily: Conclusion

To visit these Castles in Sicily is to undertake a pilgrimage through stratified time, to stand in spaces where the accumulated weight of history presses against the present with almost physical force.

Each fortress offers not merely panoramic views and architectural interest but an opportunity for contemplation, for escape from the quotidian into realms where the past remains palpable, where stone and story interweave into something approaching the sacred.

Pack comfortable walking shoes, for these castles demand physical engagement—steep staircases, uneven cobblestones, ramparts without railings. Bring water, sunscreen, and a sense of reverence.

Allow time for solitary wandering, for sitting in silence within ancient chambers, for letting the accumulated centuries seep into your consciousness like groundwater infiltrating limestone.

The best castles in Sicily are those you approach as a witness to the enduring human need to build, to defend, to leave some mark upon the earth that outlasts our brief transit through time.

This was just a quick look. There are many more castles in Sicily, such as this one in Castelbuono.

This was just a quick look. There are many more castles in Sicily, such as this one in Castelbuono.(November 3, 2025)

Recent Articles

-

Taormina: Is It Worth It on Your Sicily Itinerary?

Feb 07, 26 11:11 AM

Wondering if Taormina belongs on your Sicily trip? Explore beaches, shopping, and sights—then choose well. -

Car Rental in Sicily: A Traveler’s Guide

Feb 04, 26 01:09 PM

Planning car rental in Sicily? Learn costs by season, insurance basics, required documents, and more. -

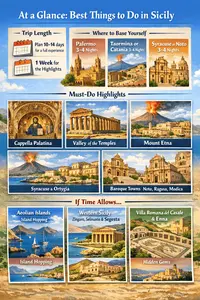

The Best Things to Do in Sicily, From Antiquity to the Present

Feb 01, 26 09:01 AM

Explore the best things to do in Sicily through historic cities, Greek ruins, volcanoes, islands, and landscapes

Follow MANY FACES OF SICILY on Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky & Tumblr

Contact: vesa@manyfacesofsicily.com